Two concrete stones inlaid with brass plaques mark the lives of Phillis and Peter, an enslaved couple who lived in Longmeadow in the 18th century.

Reminder Publishing photos by Sarah Heinonen

LONGMEADOW — Two-hundred fifty years after the death of an enslaved couple in Longmeadow, two stones that bear witness to their lives have been set into the ground in front of the First Church of Longmeadow.

The stones are part of The Witness Stones Project, an educational nonprofit program that helps groups research and document the lives of enslaved people. The Witness Stones Project was brought to Longmeadow through a partnership between the Longmeadow Historical Society, the First Church Social Justice Committee, and Williams and Glenbrook middle schools. It was funded through a grant from Mass Humanities, a private entity supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mass Cultural Council.

The Witness Stones Project in Longmeadow focused on two enslaved people: Peter and Phillis, two enslaved people who married and had a child, despite being enslaved by different people and not being allowed to live together.

Seventh-grade students researched the lives of Peter and Phillis using records and other contemporary documents, including the diaries of Rev. Stephen Williams, the town’s first reverend and Phillis’ enslaver.

The two brass plaques with details of the couple’s lives, were inlaid into concrete blocks. On Peter’s plaque is inscribed his name, years that he was known to have been enslaved in town, “husband of Phillis,” his work as a “farmer, herdsman,” and the words “enslaved in Longmeadow.” Phillis’ plaque is similarly inscribed, but rather than list her occupation, it reads “mother, noted for her honesty.”

Phillis first appeared in local records in 1728, and Peter, six years later. Both died in 1774. Coincidentally, the stones were placed on May 22, the anniversary of Peter and Phillis’ 1744 marriage.

The blocks were sunk into the ground about three feet. “These are permanent reminders of the history and humanity of Peter and Phillis,” said First Church Rev. Doug Bixby. “May it help us confront the racism in our hearts.”

Addressing the students, Bixby said, “The work you all have done as students is simply remarkable.”

The curriculum for the project was written by the students’ teachers. Superintendent M. Martin O’Shea said he was proud of the work done by the students.

“We want learning to be really highly engaging and active. And to learn about your own town … ,” O’Shea said, opining that the information and the lessons will have a lasting impact on the students.

Melissa Cybulski of the Historical Society encouraged the students in the church to look around and take notice of the left side of the balcony, where enslaved people would have been relegated during church services. Peter and Phillis were married in the room they now sat in, she said. They lived in homes along what is now the Town Green.

Cybulski shared that the textbooks from her days as a student omitted information about slavery in New England, propagating the idea that slavery was practiced exclusively in the American south. Because of the Witness Stones framework, these students now knew differently, she said.

“When we know better, we do better,” Cybulski said.

Students took turns sharing information about the couple through biographies, poetry, prose and even a short historical fiction story that depicted a scene in the life of Phillis, Peter, Williams and Capt. George Colton, Peter’s enslaver. They also created art, which was on display in the church hall.

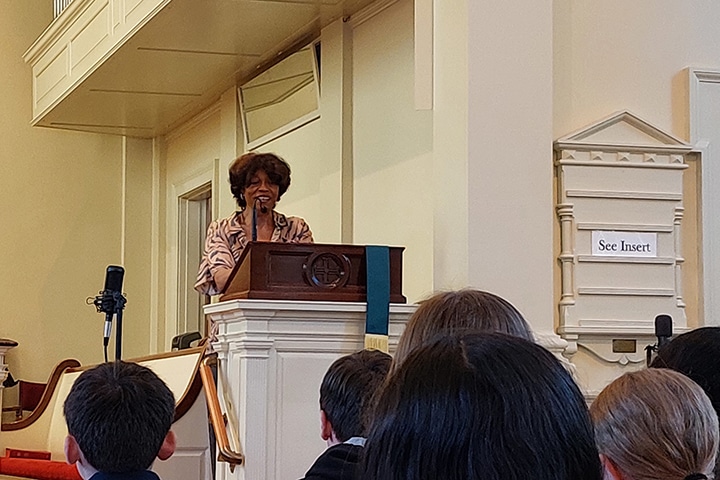

Former Connecticut state Rep. Pat Wilson Pheanious, whose ancestors were the first to be found and recognized by the Witness Stones Project, spoke to the students, saying, “The curiosity you guys and ladies showed, the interest, makes me so proud.”

She later told Reminder Publishing, “It’s several hundred years late, but racism is still with us today. Its important students recognize that these issues are not from long ago.

Wilson Pheanious said her ancestors were first enslaved in Connecticut in 1227. “My family was here before there was a country,” she said. She explained feeling as a child that, “I wasn’t African, but I wasn’t fully American either.” Leaning about her family’s past and being able to trace her family history this country has made her more “patriotic.” She said it is important to her that other children “have that greater understanding of who they are and their history.”

The ceremony was rounded out with a rendition of the spiritual, “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” sung by John Thomas, the church’s bass/baritone soloist.

The first step in this project happened in May 2022, when the Longmeadow Historical Society and the First Church Social Justice Committee researched the lives of enslaved peoples in Longmeadow for a program titled “Say Their Names.” A total of 16 people were found through that project, including Phillis and Peter. The schools and organizations that worked together on the Witness Stones Project plan to honor all 16 people over the next few years.