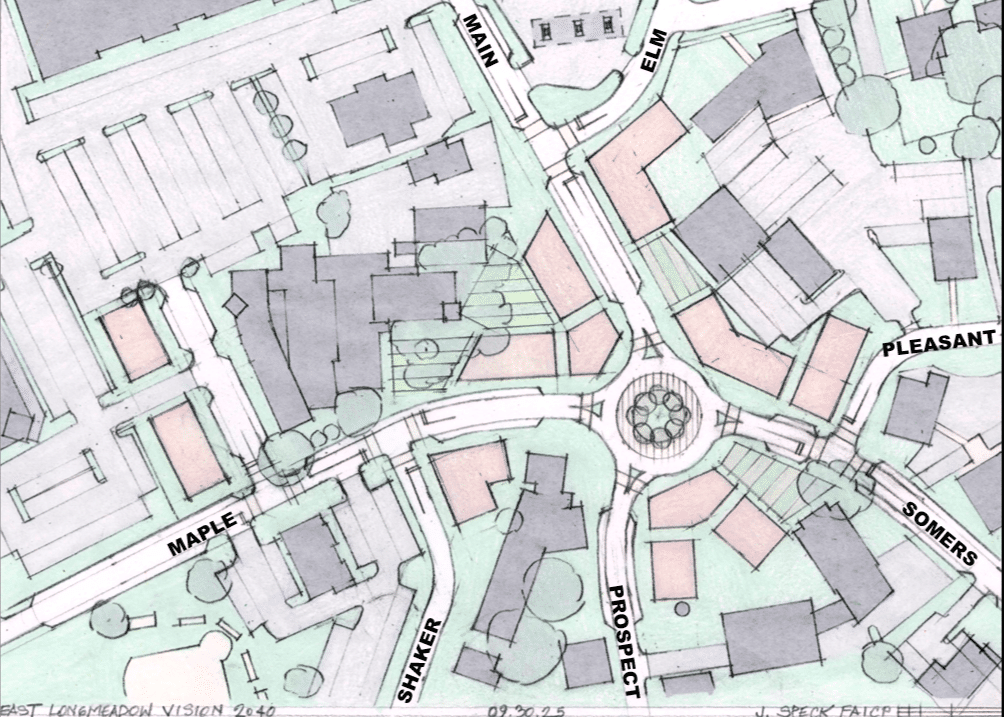

An overhead image of the East Longmeadow rotary now and urban planner Jeff Speck’s vision of a walkable solution.

Reminder Publishing submitted photos.

EAST LONGMEADOW — Over the past 20 years, there has been a movement to make downtowns livelier and safer by making them more walkable.

About 30 people came to the Pleasant View Senior Center on Sept. 30 to hear Jeff Speck talk about the need for more walkable towns and present one version of what that might look like in East Longmeadow.

Speck is a city planner and author of “Suburban Nation,” “Walkable City,” and “Walkable City Rules,”

Bringing in Speck, who is also a principal at the urban design and consultancy firm Speck Dempsey, to look at the downtown area is not part of a specific plan to create a center town district, Deputy Town Manager Rebecca Lisi said. Instead, it is more about creating a vision for what a walkable downtown and rotary might look like. Both Speck and Lisi emphasized that the ideas Speck presented are not “the plan,” but are potential ideas for how the rotary could become walkable and breathe life into the downtown.

Speck said that walkability is a “window into making better places.” East Longmeadow has all the ingredients for a walkable downtown, he said. It just requires organization. He explained that the need for walkability can be looked at in terms of finances, health and the environment.

In 2010, Speck said, the average American spent 20% of their income on transportation costs, with working households spending up to 40%. “By choosing to tie our mobility to the most expensive, most inefficient way to get around, which is each person in their own car, we’ve burdened ourselves with the tremendous cost of moving around.” He cited a Harvard study that found Massachusetts residents spend $12,000 to own and operate a vehicle, and $14,000 per year in taxes that go to maintaining roadway infrastructure. The taxes, he noted, are paid by people, whether they own a vehicle or not.

When it comes to how towns are designed, Speck said, “We have engineered out of existence the useful walk.” Not walking to complete daily tasks and errands has contributed to obesity and the illnesses that go with it, he contended.

Another health impact comes in the form of accidents. The number of vehicular accidents, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have determined as a leading cause of death in the United States, depend on the volume of vehicles on the road and the way those roads are designed, Speck said. He shared statistics showing deaths per 100,000 people due to vehicular accidents in major cities such as New York City, San Francisco and Orlando, are a fraction what they are in suburbs. Further, he noted that the trend toward SUVs and trucks has made driving more dangerous because the further the hood is from the ground, the harder it is to see children in front of the vehicle.

Of all the behaviors people adopt to try to live more sustainably, Speck said living in a walkable neighborhood may be one of the best practices individuals can perform for the environment. While electric vehicles are better for the environment than those powered by combustion engines, Speck noted that 89.5% of the particulate given off by vehicles comes from the tires and brake pads. Aside from that, it takes more energy to create an electric vehicle than a non-electric one. “Electric cars aren’t the solution,” he said. “Driving less is the solution.”

Speck said when carbon output is measured per square mile, cities seem to be the worst offenders because there are large numbers of people living in a relatively small area. However, if carbon is measured per household, data shows that people living in suburban and rural areas contribute far more carbon because they must drive everywhere.

That is no accident, Speck said. During the Industrial Revolution, people moved out of polluted cities and into what would become the suburbs. The idea of separating land according to a single use gained traction and became the standard zoning model across the country. This developed at the same time as vehicles became popular, as vehicles were needed to traverse between the separated areas of land. However, Specks said, in recent decades, the thinking has swung back, away from spread put “sprawl” toward a “traditional neighborhood” model in which vehicles and the challenges that come with them are not as needed.

“The less we’re dependent on cars, the healthier we’ll be, the wealthier we’ll be, the more resilient we’ll be,” he said.

How to make walking attractive

There are three key factors in making an attractive area for people to walk: usefulness, safety and comfort. “The walk has to be as good as the drive,” Speck said.

With a traditional neighborhood model of planning, there is a variety of housing options, as well as places to shop, dine, recreate and work within a half-mile to one-mile area. Living in such a neighborhood makes it easier to walk to a destination than drive, Speck explained. In downtown East Longmeadow, he said, there are a variety of offices, retail, dining, schools and recreation. The one thing that is in short supply is housing, and what does exist is almost exclusively single-family residences.

One thing the area has in abundance is parking, but it is not in the right places, Speck said. Using overhead satellite images, Speck pointed out that the lot at the Center Square Plaza is used regularly, but the parking spaces at the end of Crane Drive and Baldwin Street remain largely empty. Further, he said, the library is situated facing a parking lot, rather than a main road, as it is in most towns.

Sharing images of classic main streets in small-town America and roads in famously walkable cities around Europe and Asia, Speck explained that people are drawn to narrow streets with buildings on either side. The buildings do not need to be taller than two stories for the effect, he said. East Longmeadow’s Center Square is wide and fairly flat, with buildings set back from the street and expanses of grass or paved lots.

When it comes to safety for pedestrians, Speck said small blocks with fewer lanes lower the speeds at which people drive. East Longmeadow already has this infrastructure in place, he said, although the area around the rotary is arranged in “more of a spiderweb than a tic-tac-toe” of blocks. With small blocks, there are several ways to get to any one place, lessening the traffic congestion that is common in sprawling towns and cities.

After measuring the traffic through the rotary, Speck said that aside from the morning and afternoon rush hours, the rotary has little traffic, with vehicles passing through it an average of once every six seconds. Nearly all the roads that lead into the rotary see about 10,000 or fewer vehicles per day, which can be carried by a two-lane road. North Main Street is the exception, and Speck said its 15,000 cars per day can be supported with the addition of a turning lane. This infrastructure is already in place.

Speck called it a “good start” and assured the audience, “You can have the downtown you want without more congestion.”

A plan

Speck shared a draft of what the rotary could look like, eliciting interested murmurs from the audience. There are four key elements to the plan. The first is to reduce the number of roadways at the rotary. “There’s just too many points coming together in one place to ever function well,” he said.

Instead, he suggested minor adjustments that would create “doglegs.” With the addition of slight curves, Elm Street would connect to North Main Street before the latter reaches a smaller roundabout that would be offset slightly from the existing one. Similarly, Pleasant Street would connect to Somers Road and Shaker Road would connect to Maple Street, which would continue into the town center. With this configuration, only four roads would meet at the roundabout, creating a flow of traffic that is easier to navigate, Speck said.

While most of the Center Square Plaza would remain untouched, Speck suggested creating a road off Maple Street in front of the library, where there are currently parking spaces. This would place a feature of the town on a street, instead of hidden behind the Town Hall. Rather than lose parking, Speck said the streets are wide enough to add parallel parking. Parallel parking “puts people on the sidewalk” and is “an essential barrier of steel protecting the sidewalks,” he said. He said it has been shown that cars lining a street make people feel safer and they are more likely to sit at tables along the sidewalk or walk from place to place.

Shrinking the rotary into a roundabout opens space that is currently paved roadway. To introduce the comfort and attractiveness of narrow streets, Speck suggested the town partner with developers to add buildings in the space freed up by the adjusted road layout, what he described as “this land you created out of thin air.” He estimated 12 new buildings could be added to the downtown, supporting businesses on the ground level and apartments above. Alternatively, some of the buildings could be residential townhouse-style rowhouses. This would add to the variety of housing available in the town center. He added that the town could use zoning to ensure the land is developed in keeping with its priorities and values.

“It’s doable,” Speck said, but cautioned, “It will not be doable immediately.” He estimated it would take about 15 years to create all the aspects of the plan he presented. Again, he reminded people that his was just one idea of what could be done with the East Longmeadow rotary.

Cautious optimism

During the question-and-answer period following the presentation, people expressed optimism about the ideas Speck had proposed. “It solves the traffic in town center,” said Tim Manning.

“I enjoy the vision,” said another person, before asking how trucks from a group of warehouses proposed for 330 Chestnut St. would travel through the roundabout. Speck explained that there is a cobblestone area around the center that larger trucks can drive on. The center of the roundabout is relatively flat, which also allows emergency vehicles to drive over it if needed, he said.

When asked about congestion, Speck reminded the person that the rotary handles 2,800 vehicles per hour. The proposed roundabout could accommodate 1,200 cars per hour at each of the four connections.

A resident complimented the narrow roads, before asking if the dog legs will require private land to be taken. Speck said the Elm Street dog leg can be created without taking any land. The Pleasant Street dog leg requires a small “slice” of grass in front of Key Bank and the Shaker Road dog leg uses some of the grass in front of Chase Bank, he said. The part of the plan that would require coordination with private landowners is the addition of buildings on the grassy corner next to Maureen’s Sweet Shoppe and in front of the First Congregational Church. In the past, the town has said that changes to the rotary would require eminent domain, but Speck later explained to Reminder Publishing that urban design has made strides in the past couple of decades that have made design more flexible.

Gregory Thompson asked how to convince residents to embrace the changes. Speck responded, “The more complete your community is, the robust it is.” He said there has been something of a culture shift and reflected that he grew up watching TV shows like “The Brady Bunch” and “The Partridge Family,” in which people lived in single-family homes with large yards. The people who are buying their first homes now grew up watching “Friends” and “Sex and the City,” which depicted people living in apartments and townhouses. Yards and schools are only important in people’s lives for about 20 years, he said. Before and after that, they are often looking for smaller homes and diverse housing options, such as condominiums or apartments.

When asked about the cost, Speck said he estimated the road reconfigurations to cost more than $10 million. He acknowledged the price tag but said that if people are willing to pay for it, the town can choose to have the downtown it wants. “When cars travel more safely, it creates fewer accidents,” Speck said. “The path to both safety and limited congestion is slow, steady driving.”